Flash point- the lowest temperature at which a volatile material gives off sufficient vapor to ignite when exposed to an ignition source, such as a flame.

In layman’s terms: flash point is the temperature at which a material’s vapor ignites or flashes. The U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) requires that all chemicals transported have a flash point determined. This test is often performed on lubricants & petroleum-based materials, paint, adhesives, cleaning products, soaps, pesticides, inks, etc. Flash point is used to classify materials as flammable, ignitable, or combustible and can affect labeling, storage, shipping, safety precautions, and disposal. This property can be used to report product specifications and to determine the presence of contaminants. There are several standardized methods to determine the flash point of a material, but it comes down to two basic methods: open cup or closed cup. The US DOT provides a list of approved flash point testing methods for different liquids under 49 CFR 173.

Determining the flash point of a material requires heating a sample in a container and introducing a small flame above the liquid surface. As the temperature of the liquid increases, the vapor pressure and concentration increase. Standardized methods require the heating of the samples to reach the minimum required vapor concentration for ignition (lower flammability limit). The open cup method consists of a vessel that is exposed to air while passing an ignition source until it flashes and ignites. This method was originally preferred to assess hazards in liquid spills. However, the open cup method is now considered less precise due to the possibility of vapors escaping, which reduces vapor concentrations, and the influence of local conditions. The Cleveland, Tag, and Setaflash methods are the most common for an open cup analysis. In a closed cup analysis, the vessel is sealed off from the atmosphere and both the sample and vessel are heated to replicate accidental ignition in a sealed container (e.g. gas tank). This method is ideal for the determination of regulations because it more closely imitates real-life conditions. Closed-cup methods are more likely to produce lower flash points due to the contained heat and are easily reproducible. The Pensky Martens, Abel, Abel-Pensky, Tag, and Setaflash are frequently used for closed cup analysis.

There are manual and automated flash point testing methods and apparatuses. During manual flash testing, an operator monitors, stirs, controls the temperature, and visually determines when a flash has occurred. As one can presume, this leaves plenty of room for error. Automated flash testing uses electronics, software, and mechanical actions to mimic the operator’s actions. Many labs favor this type of testing due to reduced time and labor, and increased accuracy.

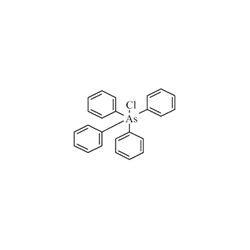

Flash point standards are tested and certified against standardized test methods (e.g. ASTM D93). These standards are used to calibrate the laboratory flash point instruments being used to provide reference points for unknown flash points. These standards must be high purity to provide the most accurate reference point possible and are widely available for purchase.

Flash point and boiling point are used conjointly to determine the degree of hazard of a flammable liquid. The degree of hazard determines the material’s Packaging Group (PG). According to the US Census Commodity Flow Survey, Hazard Class 3 flammable and combustible liquids are the most shipped types of hazardous materials each year. The US DOT Hazardous Materials Regulations (HMR) states that a liquid with a flash point above 60°C should be handled with extreme caution.

Packaging Group classification indicates the strength of packaging required to contain the material and shipping & handling precautions that must be taken. Packaging groups are divided into three: PG I, PG II, and PG III. PG I is the most dangerous, while PG III is the least. Hazmat employees use flash points to measure the risk of an explosive or ignitable material forming when a liquid escapes its packaging. Therefore, choosing proper packaging is crucial.

Improper packaging can lead to hazmat employee injuries, environmental contamination, damage to the transportation vehicle, and damage to nearby material due to incompatibility. Closure instructions for packaging must be closely followed and are determined by the type of packaging needed. Packaging is also dependent on the quantity of material that is being shipped. Most hazardous materials are required to be shipped in UN Specification Packaging, or POP (Performance Oriented Packaging), and labeled appropriately.

Packaging group information for materials can be found in a United Nations database. These packaging materials are subject to multiple performance tests for design, strength, and usage compliance with 49 CFR 178. Some of the tests they undergo include, but are not limited to:

- Drop Test

- Stack Test

- Vibration Testing

- Edge Crush Test

- Leak-proof Testing

- Pressure Differential Testing

UN Specification codes have assigned signifiers to indicate a package’s packing group suitability.

- X- PG I, II, and III (This is the most stringent packaging)

- Y- PG II and III

- Z- PG III (This is the least stringent packaging)

Packaging must always indicate a maximum quantity of hazmat that can be shipped within it and usually the modes of transportation it is compliant with. Not only does the packaging need to be labeled appropriately, but any transportation vessel carrying hazardous material must have the correct pictograms. Hazmat employees must be familiar with these warnings and the meanings behind them to accurately report what is being transported and the possible risks associated.

According to the federal hazardous materials transportation law (49 USC 5101), anyone who performs any hazmat function (e.g. shipping departments, freight forwarders, and subcontractors) must be hazmat trained and certified. This certification must be updated once every three years. These precautions are taken to ensure the safety of hazmat employees, the environment, and all material being transported concomitantly.

Even though flash points are primarily reported for product purity and specifications, it is important to remember that this property determines all the logistics behind shipping and handling. Flash point testing methods and standards are crucial to obtaining accurate values for safety precautions. Next time you see a pictogram indicating a material being transported is flammable, remember that there is a known flash point and to be extra cautious.

Citations:

Experimental determination of flash points of flammable liquid ... - INERIS. (n.d.). Retrieved March 30, 2023, from https://hal-ineris.archives-ouvertes.fr/ineris-00976242v2

The Federal Register. (n.d.). Retrieved March 30, 2023, from https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-49

Packaging your dangerous goods. (n.d.). Retrieved March 30, 2023, from https://www.faa.gov/hazmat/safecargo/how_to_ship/package_for_shipping

Stoehr, D. (2017, April 07). Flash point for classification of us dot flammable and combustible liquids. Retrieved March 30, 2023, from https://danielstraining.com/flash-point-for-classification-of-us-dot-flammable-and-combustible-liquids/

What is flash point for class 3 flammable liquid. (n.d.). Retrieved March 30, 2023, from https://www.lion.com/lion-news/october-2021/what-is-flash-point-for-flammable-liquids#:~:text=Under%20the%20United%20States%20Department,F)%20is%20a%20combustible%20liquid.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)